Wiltshire Settlers on the Weymouth (1820)

After the end of the Napoleonic Wars those British soldiers who survived found an economic crisis at home and very few jobs to return to. To make matters worse, in 1815 the British Government passed the Corn Laws, which levied taxes on imported grain in order to protect the interests of the landowners. Wheat was in short supply following several bad harvests, and the price of bread became prohibitive for the working classes. At this time all responsibility for poor relief fell on the parish authorities; the Speenhamland system, dating from 1795, was a ‘top-up system’ based on the price of a loaf of bread and the number of children in the household. In practice wages of those in work, especially in agriculture, tended to remain low, as employers left it to the parish authorities to augment starvation wages. It was also said at the time that the system encouraged couples to have more children so the family could claim more poor relief.

In the carve-up of land following the Congress of Vienna, at the end of the war with Napoleon, the Cape of Good Hope was ceded to Britain and was ruled by a governor under the jurisdiction of the Colonial Office. The Colonial Secretary at this time was Lord Bathurst, who in July 1819 persuaded the British government to put £50,000 into an emigration scheme which would fulfil three main functions. Firstly, it would establish the supremacy of English speaking settlers over the Dutch. Secondly, by concentrating the new settlements in the eastern part of the province, the Colonial Office hoped to establish a strong farming community capable of withstanding the border raids of the native Xhosa, thus increasing the security of the colony. Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly as far as the government of the day was concerned, the emigration scheme was designed to boost popularity at home at a time of rising unemployment, a trade recession following the wars in Europe, and general social unrest.

The Colonial Department wanted to make sure that land in the Cape would only be granted to those with enough capital and expertise to develop it, so when the scheme was first announced it was restricted to organised 'parties' of ten or more men, selection being given to men who could afford to engage and maintain a party of at least ten able bodied labourers over the age of 18. The head of each party would receive a free passage and food on the journey and on arrival would be given 100 acres of land for each man in the party. If they cultivated the land for three years they would be given full title, and the £10 deposit required from each man prior to departure would be refunded in instalments after arrival, either in cash or in rations to tide them over until the first harvest. (1)

Some sixty parties set sail for South Africa on seventeen ships from various parts of the UK between December 1819 and October 1820. In practice less than a third were 'proprietary' parties where a man of capital emigrated with ten or more servants. The vast majority of the so called 1820 Settlers were 'joint stock' parties under a nominal leader where each man paid his own deposit and later farmed his own 100 acres. Often groups of friends and neighbours formed a party, and in some cases a parish would pay the deposits for groups of unemployed labourers to emigrate rather than continue to pay poor relief.

Three ‘joint-stock’ parties from Wiltshire sailed on the ‘Weymouth’, leaving Portsmouth on January 7th 1820 and arriving at Algoa Bay four long months later on 15th May. The first was led by Charles Hyman from Westbury, who described his party in a letter to the Colonial Department:

“The eleven men are persons of an irreproachable character, each having some small property and being unwilling to be in actual servitude have unanimously chosen me their Representative — if we are allowed to proceed to the Cape tho’, I will not boast of any Superior Degree of Wisdom to some of the others (who are my Elders) yet going in this Brotherly way I make no doubt by our joint exertions we shall be able to surmount those difficulties which will naturally be in the way.” (2)

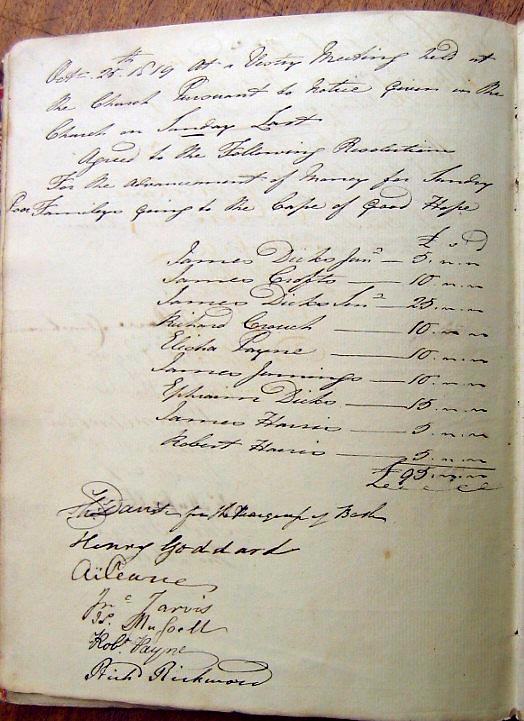

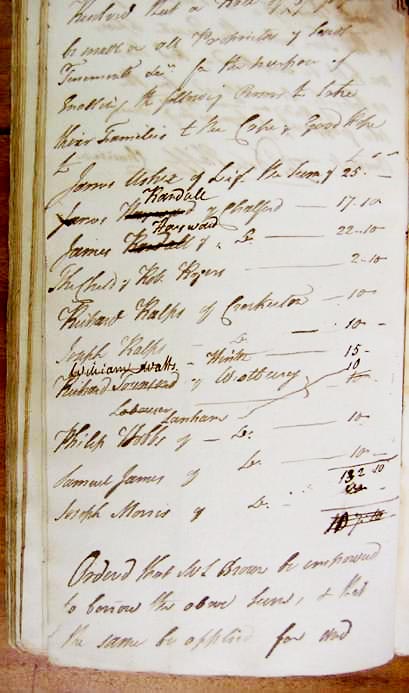

By 1819 the amount paid out in poor relief in many rural parishes had doubled since the end of the war, so it is perhaps not surprising that many parishes decided that it would be worth their while to assist families to join the aided immigration scheme. In the Wiltshire parishes of Westbury and Longbridge Deverill surviving vestry minute books from 1819 now held in the County Record Office in Chippenham show varying amounts paid to families. (3)

Longbridge Deverill Vestry Minutes, showing payments authorised for Richard Crouch, Ephraim Dicks, James Dicks Senior and Junior, Robert Harris, James Jennings and Elijah Payne from Ford’s Party(Click to enlarge)

Not all the people who appear in the vestry minutes actually emigrated. It is perhaps not surprising that some, faced with such a huge leap into the unknown, would back out. The majority of the emigrants in the party led by Edward Ford were related, and came from the area around Longbridge Deverill, near Warminster. Robert Harris was a nephew of James Dicks Senior, and a late replacement in Ford’s party was a nephew of Ephraim Dicks, a weaver from nearby Erlestoke called Robert Miles. The story of Robert Miles and his family is wonderfully described in ‘Story of a Frontier Family’ by Wendy Beal Preston.

“The young woman was carried away in imagination — the thought of a warm climate was appealing and surely with 100 acres of their own there was a chance of prosperity…and imagine, a sea voyage! But what would it be like when they got there? She had heard tell of wild beasts, and snakes…No matter, several of her own relatives were going, they must have thought it all over carefully and besides, she had Robert, always so strong, so comforting…and what was it the preacher said in church only last Sunday? ‘Trust in the Lord with all thine heart and He shall direct thy paths.” (4)

Also included with Ford’s Party were Joseph and Richard Ralph, more relations of the Dicks and Miles families, whose passages were paid for by the parish of Westbury. Most of those listed in the Westbury vestry minutes eventually emigrated in a party led by Samuel James. This included seven men originally on a list of potential emigrants submitted by John Colston from Frome, just over the border in Somerset. Colston was an army pensioner who was recalled to his regiment during the Peterloo riots of 1819. Of those listed as receiving help to emigrate from the parish of Westbury, James Hayward, Richard Hinton, James Randall and James Usher appear on Colston’s original return. (5) Philip Hobbs, Samuel James, Thomas Lanham and Robert Rogers were originally on a return filed by Samuel Watson, who was replaced as leader by Samuel James when he decided not to emigrate.

Westbury October 26 1819 (6)

Your last came to hand stating the amt. of money which would be nesasary to send you. Amting to £137:10:0 which the parish of Westbury has in contemplation of making up some of the amt for those who is not able to pay their own way which is to be settled on Sunday next, but since the first of our application our foreman Mr.Watson with three or four of the others has Rinag’d but should it meet with your approbation I will ingage to fill up Mr.Watson’s station as foreman & also get the compliment to fill up those who has left. Your answer to the above will greatly oblige your obed. Serv’t.

Sam’l JAMES

NB Please to Say the Day when the money must be sent & also when it will be nessasary for us to come to London or where we embark.

It is clear from Samuel James’ correspondence that the Westbury settlers did not know until the very last minute where they were to sail from, and the sense of uncertainty must have been very great. Even more so for Richard Hinton and Thomas Lanham, who did not get final clearance to join James’ Party until the last minute, when the ship was almost ready to sail, and they appear as the last two names on the muster roll of the Weymouth. We can only imagine what an anxious time those families must have gone through.

Gosport 26 Dec (7)

In Apply to John Hopkins letter dated 22nd instant from Mr. Goulburn acceptances of him and his wife and family in the substituted of William Watts and family By my Recomention I therefore strongly recommend him as a usefull an fit man for this Emigration to the Cape of Good Hope. I also state that Richard Townsend and family is not coming but in substituted for them this Gentleman of Westbury have sent up Thomas Lanham Plaster & Tiler aged 30 his wife aged 24 and children aged 2? Also Richard Hinton Blacksmith aged 34 his wife aged 33 their daughter Rebecca 10 George their son age age 7 Linard their Daur [sic] aged 3 years Jane their Daughter 6 months all waiting now at Portsmouth for your Lordship’s approbabtion upon the Busness By the Returns of Post if your Lordship think proper.

I am my Lord your Lordships humble servant

Samuel James

The first page of the Westbury Vestry Minute Book entry

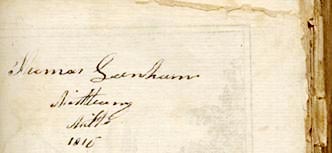

The Wiltshire settlers were for the large part impoverished, but the majority of them were not illiterate. Much of what we know today about life for the early settlers is derived from diaries written at the time, and we can see that although Samuel James’ spelling was far from perfect he was more than capable of conducting correspondence with the Colonial Office on behalf of his party. Thomas Lanham may well have had some reading matter with him to while away the hours while waiting for confirmation that he could sail. John Fuller in Canada now has in his possession a 1766 edition of the Pilgrim’s Progress which in all probability sailed on the Weymouth, inscribed by Thomas Lanham in 1816. (8)

“Most of the settlers came to their port of embarkation in farm carts and wagons, carrying some small pieces of furniture and a few cherished possessions, with their clothes and bedding in boxes. Bedding for the voyage had been provided by the authorities. The leaders of the parties took pigs, fowls and a few sheep in crates which were put up on deck. The men also had tools required for building and carpentry, and seeds for future grain crops and vegetables. The women took a few trusted home remedies, precious pieces of china and linen, some seeds of beloved English cottage garden flowers. One English mother gave each of her daughters a rose bush from her garden to take with her when she married. In this way the English ‘moss rose’ came to the Eastern Cape and some of the older farm gardens, including that of the writer, still have them.” (9)

We know from diaries written at the time and from the log of the Weymouth that it was bitterly cold, with snow in the air, as the settlers assembled in Portsmouth. The ship’s log indicates that most of the settlers went on board on December 16th 1819 and spent a white Christmas on the Weymouth. Some settlers had to be accommodated on a hulk in the harbour while ‘artificers fitting settlers berths.’ (10) On Christmas Eve snow began to fall and 569lbs of fresh beef and 80lbs of vegetables were brought aboard. It must have seemed like a fairy tale adventure, especially to the children. Samuel James, however, as well as all the worries associated with being a party leader, was also pre-occupied with his wife Elizabeth, who gave birth to twins shortly before the ship sailed. Samuel wrote to the Colonial Office from on board the Weymouth on 27 December:

My Lord

I beg leve to state that I promised to give you the neams of my two sons yesterday. I am very sorey I should be so trubelsome, the neam of the First is Samuel William James and the other Thomas James they are three weeks old yesterday & are very likely to live. But the worst is the Mother have not any Milk to suckle them which is a deal more trubel to express. (11)

Sadly his optimism for his sons was misplaced; Elizabeth James died three days later on 30 December, closely followed by baby Thomas on January 2nd 1820, with the bodies being sent ashore for burial. James Jennings from Ford’s Party also became ill and was sent ashore to Haslar Hospital in Portsmouth the day before the ship sailed, where he subsequently died. It says a lot for the tenacity of the early settlers that Samuel James was willing and able to continue to the Cape as a newly bereaved widower with a month old baby, although baby Samuel also died on January 12th and was buried at sea the following day. Mary Jennings and her 3 year old son James also continued to the Cape alone.

There was another party from Wiltshire on the Weymouth. Miles Bowker, a prosperous farmer from South Newton, near Wilton, though he was originally from Northumberland, emigrated together with seven of his eight sons (the eldest stayed behind to wind up the family’s affairs). William Bowker, though only 17, was accepted by the Colonial Office as one of the ten able bodied men; the eight other men making up Bowker’s party were all described as ‘countrymen’ from Wiltshire. M.D. Nash reports in ‘The Settler Handbook’ that one of them, John Stanford, was ‘aggrieved to find himself worse off than the parish-assisted emigrants in the party under Samuel James. He considered that he was entitled to receive a full 100 acres of land at the Cape, not the 10 that Bowker was willing to give him.’ (12) Thomas Holden Bowker, a child of 12 on the Weymouth, later wrote his reminiscences of his last days in England. (13)

“After a few days the time came for our going on board the Weymouth Store Ship as she was called. She, like our old friend the Brave, [the hulk ship on which the party was quartered while the Weymouth was made ready] had seen better days and had been a frigate, but had been taken out of the fleet and turned into a transport or troop ship. She was, however, commanded by a set of Regular Officers and crew but in a reduced number. She still had some few guns on board and looked like a ship of war. There were already many parties of settlers on board, and others going on board like ourselves. The Weymouth seemed as large as the old ship we had left but not so high out of the water, but we were soon all on board where we met a crowd of gentlemen, one of whom, a tall, good-looking man with a white [beard], had addressed my father by his name and asked him if he was any relation to Ben Bowker of the Leocadia, and upon my father telling him that Ben Bowker was his own and only brother, he appeared delighted to have found a brother of his old comrade bound to the same new country as himself. Captain Campbell of the Marine Service and my father became friends, a friendship which terminated only with their natural lives.

Upon looking about the ship you might perceive the most incongruous assortment, or utter confusion of articles. The settlers of all classes, high or low, had most of them become travellers for the first time in their lives. They were only beginning to gather by degrees that experience which was wanted to teach them how to pack up things properly and to realize what should have been left behind. Lucky appeared the ordinary class of emigrant who, having only a single chest, could sit upon it at his ease, while those who had larger possessions saw them go down into the hold or saw them piled up, creaking and breaking, to make room for more. But in a short while all these things were sent down below except some of the larger articles. My father's long carts were stowed upon the booms before the main mast. The wheels were sent below, as were the artillery wagons.

The storage of goods completed, the settlers were consigned with their numerous families, amounting to nearly 700 in number, to the small berths in double tiers arranged on each side of the orlop and main decks. The berths were occupied mainly by the women and children; the men slept in hammocks slung in a long row in front of the berths. On the upper deck the poop cabins were allotted to the more respectable families. On one side was my father's cabin with his eight sons and one daughter, while on the opposite side was a gentleman whose family consisted of one son and nine daughters. A long dining-table reaching the whole length of the poop cabin served for all purposes, and each party occupied their own section.”

As the cold of England and the sea-sickness of the Bay of Biscay was gradually left behind, and the settlers acclimatised themselves to life on board, another problem arose. An outbreak of measles claimed the lives of several children, mostly from the Wiltshire parties; James Farley from Hyman’s Party; John Crouch and Mary Ralph from Ford’s Party; Sarah Hobbs, Joseph Pinnock and Emma Rogers from James’ Party and Jane and Sarah Stanford from Bowker’s Party. It seems incredible that any of the women should have embarked on such a voyage whilst pregnant, yet there were also 11 babies born at sea whose births are recorded in the 1820 muster roll. (14) Some of these children were later given the middle name Weymouth, including Eliza Weymouth Usher born on March 10th. Anna Maria Bowker was also born at sea on 26th April, but sadly the unnamed baby girl born to Philip and Charity Hobbs on March 22nd, just six weeks after they had seen their daughter Sarah buried at sea, did not survive and died on April 13th. In addition to the infant deaths, Ephraim Dicks died on April 26th, almost at journey’s end, and was buried in Cape Town before the ship sailed onward to Algoa Bay. Jane Dicks, wife of James Dicks Senior, also died on board.

The ship took on water and provisions in the Canary Islands and although the settlers could not go ashore it must have been very welcome to have fresh fruit and a change from an extremely monotonous diet. The log entries for the 25th - 27th January are fairly typical.

Tues 25 January

Am: Fresh breezes and cloudy

4: short sail and hove to

8: centre of the town of Las Palmas Gran Canary WNW

11: shortened sail and came to with SB in 23 fathoms. Veered to 80 fathoms

NE point of Gran Canary N6E1/2E Centre of the town West

Bearings and Distance at noon. Single anchor off the town of Palmas

Pm: Moderate and fine

Furled sails down royal yards

Employed sending empty casks on shore for water in shore boats

Midnight moderate and cloudy

Wed 26 January

Am: Moderate and fine

4 do. weather. Rec’d water from shore boats. Killed a bullock wt 342 lbs Rec’d 6 oxen and a quantity of fruit and vegetables for the settlers

Pm: Employed receiving water. Departed this life Sarah Stamford settler’s child

8: Light winds and fine

Midnight: do. weather

Thu 27 January

Am: Light breezes and cloudy

4: do. weather. Employed receiving water in shore boats. Killed a bullock weighing 660 lbs. Departed this life Sarah Whitehead. Committed the bodies to the deep.

Pm: Employed receiving water

Midnight: do. weather

On Tuesday 25th April Table Bay was sighted, doubtless to the huge excitement of all on board. Captain Campbell’s party of settlers disembarked at Cape Town but all the Wiltshire settlers, with the exception of Benjamin Trollip from Hyman’s Party, continued on to Algoa Bay. The last leg of the journey was to be even more crowded, as two parties of settlers from the Stentor transferred to the Weymouth in Table Bay and are recorded on the Weymouth’s muster roll. The ship anchored in Algoa Bay on May 15th, but the settlers did not start disembarking for another five days. The Wiltshire parties were discharged on May 23rd and settled in Lower Albany. M.D.Nash notes that Ford, Hyman and James’ parties were ‘the only settler parties to remain virtually intact under their original leaders during the settlement’s first three years.’

They had finally arrived, but the big adventure was just beginning, and many trials and tribulations lay ahead. The following was written by an 1820 settler who did not sail on the Weymouth, but his reaction on arrival was doubtless typical of all the Wiltshire settlers.

“It was a forlorn plight in which we found ourselves when the Dutch waggoners had emptied us and our luggage on to the green-sward and left us sitting on our boxes and bundles under the open firmament of heaven. Our roughly-kind carriers seemed, as they wished us goodbye, to wonder what would become of us. There we were in the wilderness; and when they were gone we had no means of following, had we wished to do so. We must take root and grow, or die where we stood. But we were standing on our own ground, and it was the first time many could say so. This thought roused us to action — the tents were pitched — the night-fires kindled around them to scare away wild beasts, and the life of a settler began.” (15)

by Sue Mackay

3 x great granddaughter of Philip Hobbs, William Bartlett and Selina Hayward

This article was first published in Genesis, 2005

Sources:

1. General information about the 1820 emigration scheme and listings of the parties to be found in ‘The Settler Handbook’ by M.D.Nash, Chameleon Press 1987.

2. Original at the National Archives in London CO48/43 and reproduced in ‘The Settler Handbook’

3. Longbridge Deverill Vestry Minutes 1020/55 and Westbury Vestry Minutes 548/2, at the Wiltshire and Swindon Record Office. Reproduced by kind permission of the WSRO. Please note that the Westbury minutes in particular are in a very frail condition and may not always be produced. The author has digital copies.

4. From introduction to ‘Story of a Frontier Family’ by Wendy Beal Preston, 1983

5. Return of Settlers Proceeding to the Cape of Good Hope, National Archives in London CO48/47

6. Letter from Samuel James to the Colonial Office, National Archives in London CO48/44

7. Ibid.

8. Website of John Fuller at http://fuller-ocean.benbus.co.uk/Gallery.htm

9. ‘Story of a Frontier Family’ by Wendy Beal Preston, p.20

10. Log of H.M.Storeship Weymouth at the National Archives in London ADM51/3543.

11. Letter from Samuel James to the Colonial Office, National Archives in London CO48/44

12. ‘The Settler Handbook’ p.47

13. Found on http://www.1820settlers.com/ under Topics: ‘Last Days in England’ by Thomas Holden Bowker. Transcribed from Ivan Mitford-Barberton's book, "The Bowkers of Tharfield", by Paul Tanner-Tremaine.

14. Muster Roll for the Weymouth at the National Archives in London ADM37/6146

15. From ‘The Reminiscences of an Albany Settler by H.H. Dugmore (1810-1897), one of the 1820 settlers, originally given as an address in Grahamstown on the 50th anniversary of the settlers’ arrival and since re-published by Grant Christison in 1990.

- Hits: 31151